When I heard that Lisa Mottolo was coming out with a book, and the book’s title was How to Monetize Despair, just out from Unsolicited Press, I knew I wanted to talk to her about her work. I’ve been a fan since 2021 when we published Mottolo’s poem “Isolation // Description of Upstate New York.” A native of Schenectady, NY, Mottolo’s visceral collection has been described as “dark, playful, and surreal” by Mary Biddinger. Mottolo and I talked through the magic of electronic communication about her poetry, self-help books, living in the past, and birds.

This is a question that I enjoy asking each of my interviewees: where on this earthly plane are you while answering these questions (mentally, physically, emotionally)?

I’m currently at an airport in Cleveland, Ohio, and am soon to be home in Austin, Texas. Mentally, I’m the best I’ve been in my life.

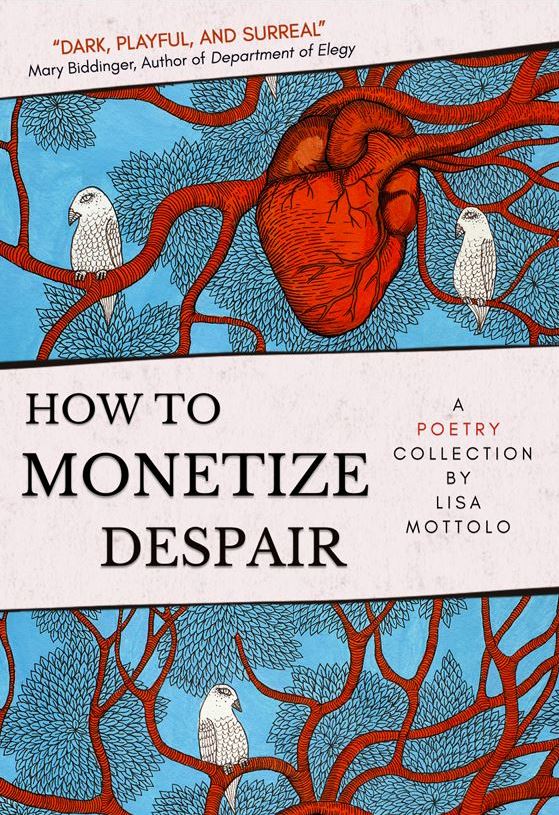

The cover of How to Monetize Despair is so vivid. There are human hearts (or at least what I imagine to be human hearts) that decorate the page with vivid reds, as arteries sprawl out, posing as trees. White birds on red limbs and plush blue leaves blend in with the rest of the page behind it. What is the name of this piece of art and why did you choose it as the cover for your book?

This piece is a hand drawing titled “Heart Tree” and it’s by the Ukrainian artist Elena Vizerskaya. I came across this piece while looking at an art site, and it immediately reminded me of my poem “Obituary for a Small Parrot,” which says, “I drove home from the vet with her body in a cardboard/ box, and the trees marched past with stiff brown coats, / some demanding I scrape a thick string of blood / from my heart /and present it as an explanation for my neglect.”

I also thought it would be a good representation of my book because it contrasts the slow and graceful beauty of nature with the complicated, sprawling soul of humanity.

As I read the section names in your book, “How to Be a Flock of Burning Canaries,” “How to Remove the Kettle from the Flame Right Before its Hideous Whistle,” and “How Not to Succumb to Mediocrity,” I found myself thinking that this was formatted as if it were some sort of self-help book. Was that your intention while writing this book? What are the purposes of the three different sections? You even poke fun at self-help books in your poem, “Don’t Forget to Take Your Heart Medicine.” Is How to Monetize Despair an anti-self-help, self-help book?

I have a love-hate relationship with self-help books. They’re kind of corny and can get away with being poorly written, as long as they are conveying valuable information. They’re the opposite of poetry. Poetry must be well-written and can get away with saying nothing.

I used to have a project called “Titles of Self-Help Books I’ll Never Write,” which was a series of strange or ironic self-help book titles that I sometimes made covers for. One of the titles was “How to Monetize Despair.” This title was created in recognition of artists and potential artists who feel they have nothing to offer besides their experiences of despair and are desperately seeking a way to express and monetize (for the sake of livelihood) their single offering. This then became the title of a poem, and I ended up liking it enough to make it the book title. Then I decided to turn the entire book into a pseudo self-help book because I thought it’d be amusing.

As far as the three sections, they are loosely organized in this way:

Part I: How to Be a Flock of Burning Canaries: An introduction to the many slow punctures of death and disappointment.

Part II: How to Remove the Kettle from the Flame Right Before its Hideous Whistle: A series of intimate looks at people and what they do.

Part III: How Not to Succumb to Mediocrity: An appreciation for flora, fauna, and what these things mean to us.

“How to Write About Trauma” shows a lot of emotion that is carried out through many of the pages that follow. The loss of a parent, survivor’s guilt, and life after loss are shown in a non-rhyming couplet format. Being the opening poem in your collection, was there a reason that you made this one the first one?

I made this the first poem because I thought it would provide context to help a reader better understand the poems to come. Many of the poems are about my mother and many portray pain and suffering, and I didn’t want these to exist in a vacuum.

As I read through your poems, I sit here awestruck at these beautifully written, tactically formed poems that are filled with both vivid and visceral imagery. “Upstairs, the carpet is half-removed and folded over, and my blood from two decades ago is a splash in the corner,” (“The Loneliest Blue is the Reflection of the Sky”), “ … plopping into pink clumps/ on the white plate like newborn/ mice,” (“White Plates”), and “It tastes of the pink underneath a flaked fingernail…,” (“American Summer”) are a few great examples of this. How do you come up with these lines? What is your writing process?

I honestly think these lines come from reading other poetry. Reading an interesting piece of imagery fuels me to write my own. Pretty much every time I’ve written something, it has come immediately after reading a piece I really enjoyed. A good number of my poems have been inspired by reading Mary Ruefle, Mary Biddinger, Elisa Gabbert, and Diane Suess. I also think I was born a very sensitive person with colorful internal experiences that I find rewarding to express.

Going off of this question, I want to talk about your allusions to birds. There are birds in nearly every piece, some mention of them lurking between your prosaic and poetic lines. I am getting some serious 19th-century flower allusion vibes here. Are birds just birds? Are birds a connection to something bigger here? Why all of these birds?

Part of what draws me to birds is sympathy. Captive birds tend to be abused and mistreated because their needs are not understood, their noise levels can be difficult to tolerate, and they might not automatically love and respect you like some pets. For this reason, many birds end up in rescues with self-inflicted wounds, anxiety, trust issues, and no one wanting to adopt them because they’re a mess. I can’t help but relate to these creatures.

You probably won’t be surprised to hear that there is also a connection between birds and my mother. She loved birds and we almost always had a pet bird in the house. The year before she died, she brought home a Quaker Parrot, also known as a Monk Parakeet. He was olive green, one of the sweetest birds on the planet, and quickly learned many words and phrases. I didn’t have many friends at that age (13) because I was extremely quiet, to the point that some of the boys at school nicknamed me “Vow of Silence Girl.” So, this bird quickly became my best friend and brought me genuine happiness. It was like a reason to be alive. Years later when I was living on my own, I started volunteering at bird rescues and adopted a few parrots. I currently have four adopted parrots at home.

As I have mentioned in previous interviews, I am a confessional writer myself and have had a hard time reflecting on my childhood in my writing. We see in “Obituary for a Small Parrot,” “Balloon,” and a few other poems, a call back to childhood. Is writing about your past experiences, such as your childhood (an assumption that I am making off of the text) from the age that you were when writing these poems cathartic? Is it troubling to have these memories resurface? What is your process to be able to write about childhood?

I have the unhealthy habit of living in the past, but I think it’s because I’m trying to understand it and get over it. If something keeps playing in my head, I’ve realized that it’s because I haven’t wrapped my head around it yet. It took me over 15 years to stop replaying the car accident with my mother, and I think writing about it is what helped me recover.

Yes, it is usually troubling to have memories resurface, but I’ve started taking it as a cue to write about it and resolve it once and for all. I don’t find it difficult to write about these memories because they are incredibly vivid.

I love your poem, “A Philosopher Afraid of the News.” I have never read anything quite like it before and find the projection of existential and philosophic ideologies onto a cockroach, what many think is a lowly creature, kind of comical. Is this a situation that occurred in real life that inspired you to write about?

From a young age, my mother would point out tiny creatures with appreciation, and I think this made me a person who does the same. I think they’re inspiring because they are so small yet play such large roles in shaping the planet. And I love how they just crawl around minding their own business. But to the point, we had a house in Austin with a cockroach problem, and I think the story Metamorphosis was floating around in my brain. I witnessed a cockroach hide behind the garbage can in the bathroom one day, and I thought, “This guy’s got ideas… I mean, he probably doesn’t, but what if he did?”

While talking about death and loss, you make commentary on things such as gun control (“The Entire World”) and climate change (“Scarier Than Hell Ever Was”). These political topics seem perfectly placed in this book, and I wonder what your thoughts are on these poems. Do we monetize off of these things, such as we do with despair?

I think these topics fit under the umbrella of despair, or they do for me anyway. Someone responded to one of my social media posts and made a joke about poets being people who monetize despair, which is an underlying point of my book title.

Artists in general like to poke at devastation not only because it inspires them, but also because ignoring these things is a sign of a declining society. I’ve seen writers publicly denouncing other writers for writing about major tragedies because they think they’re doing it for clout. This is a harmful perspective. We have to write about these things. We have to keep these things in mind so we are taking appropriate actions in our everyday lives to prevent them from reoccurring.

Additionally, many people who feel compelled to create this type of art have had their own private tragedies that have gone unacknowledged. Acknowledging the tragedies of others is their way of creating balance in the world.

My favorite poem in this collection has to be the title poem, “How to Monetize Despair.” The reader begins the poetry collection reading about the loss of the mother, and everything comes back to the mother in the end too. It’s here where the reader sees that birds may very well be a connection back to the mother. I guess my question here is how do we monetize despair? Is there a right way to do so?

Going back to a comment I made about the origin of the title, I think despair is all some people have to offer, and for this reason, they are compelled to give it value. There are three ways to do it right:

If you’re providing relatable art that brings others comfort

If you’re bringing awareness to an issue

If you’re doing it beautifully

Even people who don’t create art are inspired by pain to succeed in monetary and nonmonetary ways. At the core of all accomplishments, I think there was an aching and a need to resolve it.

Finally, I am curious as to what other stuff you have going on right now or somewhere in the near future. Are there plans for more poetry collections? Other publications or interviews on the horizon? I’d love to hear about your publication endeavors with this book.

I’m currently working on my next poetry collection, which I’m hoping to have completed within a year, as well as a poetry workbook-anthology, which I’d like to have done within 6 months.

I’m planning on getting some readings scheduled very soon, which will mostly be online and in Austin, TX, but maybe also in Upstate NY. I don’t yet have any forthcoming publications outside of this book, but I’m working on having some very soon.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Samantha Zimmerman is an editor of Pine Hills Review and is an all-over-the-place poet with a passion for all things experimental and confessional. Her work has been featured in Sledgehammer Lit, Bullshit Lit, Discretionary Love Magazine, BarBar Lit, and The Afterpast Review. You can keep up with her on Twitter @samthezim.