I have been following Lauren Hilger on social media for some time now. When I saw that she had come out with her new book, Morality Play, a collection that dances along the lines of feminism, coming to age, history, and the ideals of beauty, I knew that I had to read it.

Lauren Hilger is the author of Lady Be Good (CCM 2016) and Morality Play (Poetry NW Editions 2022). Her work has appeared in BOMB, Harvard Review, Kenyon Review, The Threepenny Review, Poetry Foundation’s online archive, NEA’s Poetry Out Loud, and elsewhere. She has also received fellowships from the Hambidge Center and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and was named a Nadya Aisenberg Fellow in poetry from MacDowell.

In our interview, Lauren and I discuss all things historical literature and historical humanity, ideals of beauty, the dangers of deep research, and a Britney B-side.

One of my favorite things to ask the writers that I interview is where are you when you are answering these questions? Where are you in the world? Where are you mentally? What is going through your mind right now?

Hilarious you ask. I am on my couch right now but a few hours out from heading to the hospital to give birth. Mentally, I’m not there yet! I feel really grateful though to have this bit of space beforehand, to give time answering questions about a book I wrote in a very different place. Regardless of significant life changes, (literally about to have a new identity) I still feel close to the material. This book is a signature in a way.

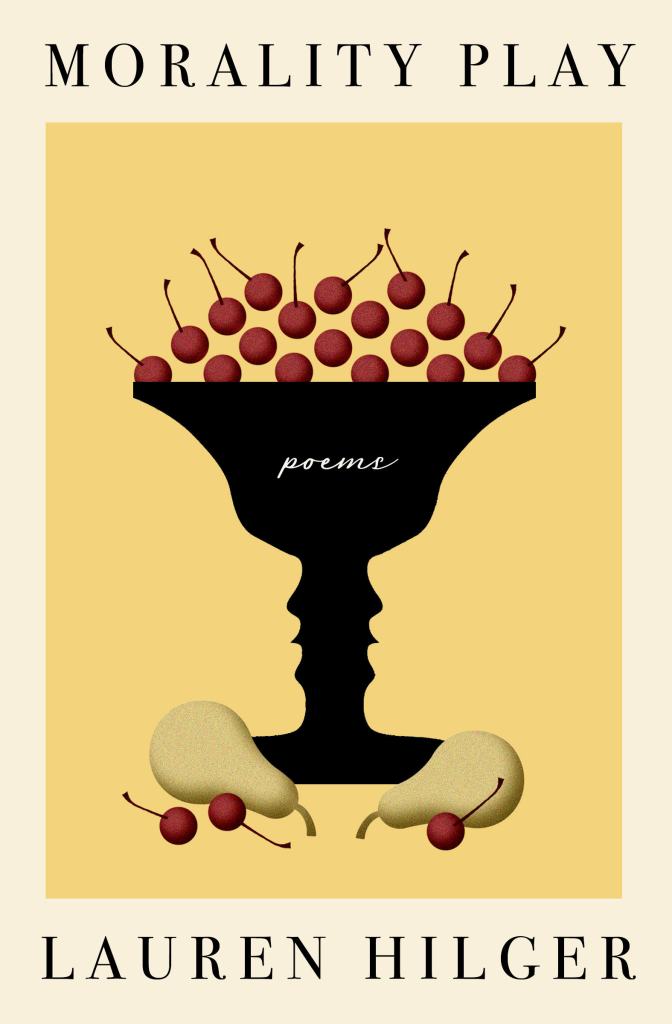

The cover of your book, Morality Play, portrays a chalice of sorts with cherries overflowing inside the black cup onto the yellow surface below. We also see two contrasting pears lying at the bottom of this image. Further research showed that these fruits are often associated with femininity, rebirth, reincarnation, and fertility. The shape of the pear is often associated with female physicality. What made you choose this picture as your cover? What about this piece of art speaks to you? What do you think of it?

Oh, I love this read, especially the pear shapes, and reincarnation! My publisher worked with a really talented designer, Peter Selgin, whose work I admire. Highly suggest scrolling through his portfolio—love Moby Dick particularly. Finalizing a book cover, especially when working with a press, is a collaboration. With my amazing editorial team, I felt very heard but also the ideas tossed around by them were so smart. My taste, early on, was leaning toward “hot pink” and “I want a pompon.” I’m so glad to have had other voices’ input for the final design. I can’t imagine this book without these cherries, that muted yellow, or without the trompe-l’œil faces leaning into one another.

Going off of this question, the term “morality play,” is something that is new to me. How did you come to this title for this collection? What is the meaning of this title? What is the morality here?

I liked thinking through this set of poems as a morality play, traditionally, an allegorical drama from the 15th/16th centuries, in which there are very clear and antagonistically defined moral qualities (virtue, chastity, vice, et al.) and in which moral lessons are taught. For this book, I used the content of certain years of my life. Within those years and those poems, I sensed a seeking and a muddiness of right and wrong. I knew there was a holiness but maybe it wasn’t aligned with what was most obvious.

I liked the idea of an antiquated morality play’s framework with my more contemporary themes and motifs. What is morality here is indeed the question. I kept asking! Is this an obscure premise? Sure, but I wanted that dignity and lofty contemplation around topics like Britney Spears and the club.

From the first pages of your poetry, it is evident that you write with a powerful sense of place, almost always paired with a desire to belong. Is this duality intentional? Is place important in your poetry?

Beautiful questions! I grew up with a farm landscape as a kid and have also spent 15 years living in NYC. There’s wanting to belong and there’s also the resonance of a place, even if feeling outside of it. I wanted these poems to be “real” in that they “happened.” Often that meant I’ve conflated scenes and people and places to be collages but the root of all is that it happened, somehow. That mixing might add to a sense of displacement and a hominess.

I have to say, I think this poetry collection has made me do the most research that I have ever done for any interview that I have conducted, and I absolutely loved this experience. The title of “In Praise of Folly” sounds so familiar to me when I first read it, and I learned that it was an essay written by Desiderius Erasmus in 1509. Do you think your poem reflects those ideals of Erasmus? As a reader, are we meant to make these intricate connections?

I wanted to ask: what does “In Praise of Folly” mean outside of the original text? I had read that essay as a student and had a mini-diary going alongside the text. I don’t think I meant to be irreverent and it wasn’t marginalia, I just kind of wasn’t listening to him. Then I read it for real as an adult and my notes cracked me up. I think intricate connections are personal and belong with the reader. I know very little about the source material of my favorite poems but I still feel fierce connection to them. The ghost of folly, however, or Erasmus’s arguments, exist very much in these poems. Being a reckless teen and a wholesome acceptance of that felt apt. The sections by Erasmus I actually read and responded to as a youth, with ardent underlines, are touching to me now.

“Beginningless./ We lost our shells years ago,” are two lines in your poem, “Mystery Cycle.” If the cycle has no beginning can it be a cycle? What exactly is this cycle that you are talking about?

I like how every generation thinks they’re the fastest, most modern, so tech-forward, so different from their forebears—i.e., the poets of the 1980s bragging about using the “yellow pages” as source material, not knowing how dated that would sound. Keats looking back at his hero Shakespeare like, if you could see England now! It’s wild!

There’s so much intrinsic to us that seems beginningless to me. Every generation rolling their eyes at elders and knowing how to use a machine with more aplomb. That’s kind of funny to me but also what’s fascinating is that it seems even the most sheltered adolescents of every epoch want to misbehave, try out their individuality, carve out a self, and they feel like they’re the first to do it. Is there a beginning to any of our human traits?

From talking about Austrian film directors to famous actresses, theologians, humanists, and artists, you use a wide range of historical figures in your poetry. Do you have a particular interest in philosophy?

I can’t say I know much but I would love to spend any free moment with any of the bits you list above. Moreover, I love listening to people who have deep reading habits and curiosity around topics about which I know little. I guess I always want to be confronted with how little I know. Maybe that’s why philosophy is catnip to some people (like me).

You also seem to make many connections between Ancient Greece, the Realism Period (late 1800s, early 1900s), and then modernity. Obviously, you see a connection between these very vast time periods. What is it that you are trying to do with these comparisons?

Just a few minutes ago, I was arguing each generation is the same with our judgments on the past; however, I fall into this trap, too. I do feel humans are different than we used to be, because of technology, because of how fast, how modern we are—e.g., I can type as fast as I can speak—Plato would be confused about that, for one, and had argued writing and speech are dialectically opposed. To that, I say, not anymore! Dada art and Futurism are 100 years old; that feels like an oxymoron. Sometimes I’ll read about a Bronze Age hair tie and want to cry because I feel connected to that kind of humanity somehow. Should Earth exist for much longer we, too, will be quaint figures of the past.

In the same vein, I loved your mention of the Gibson girls in “Psychomachia.” The Gibson girls were once the feminine ideal of physical attractiveness, portrayed through drawings by Charles Dana Gibson in the late 19th century. Do we find that modern-day women struggle with a version of this idealism, maybe specifically in pop culture and the new age of reality television? I know you do make a reference to Barbie at one point. Does idealism transcend all of the timelines that you talk about?

I laughed when I realized as a kid every princess I drew, every girl, every queen, had that giant updo of the Gibson girls. The curls at the brow, the height and volume of the bouffant. I didn’t know I was drawing a specific style. I thought I was just engaging with an elemental archetype. Idealism is a bit scary to me, limiting and false. All beauty hierarchies are inept. One has to learn that! The ideologies in which I swam as an ignorant child of the early 2000s are frightening but juicy to consider. How much we have to slough off.

Not only do you use these tropes of beauty, but you describe Ancient Grecian arts of the Hellenistic Period, and many philosophers and theorists ranging from Hippocrates to Aurelius Clemens Prudentius (if I am reading into this right). You use art and ideals that transcend centuries, and even millennia of culture. You even touch on 19th-century realism. Are these some of your personal interests? What do you want your readers to get from these associations? How does the goal of your text change when readers don’t make these connections?

I don’t think you can help your references. The books we write are the beliefs we learn and unlearn, the cultural phenomena that haunt us.

Personally, I love a book that makes me research further but I also believe poems to be solid and standalone experiences regardless of any connection to the references. I actually think that could be more interesting. If I’m reading someone else’s poem that references a scholar or theorist or artist I don’t know, I can make that choice to look further, but I also have the right to spend time within the poem itself and not bother with that kind of structuralist framework. Sometimes just spending time with the words and images is the kind of read I want.

Femininity and feminism seem to leak through the pages and intertwine with your words. In the first section of your book, there seems to be a lot of softened femininity trying to break the boundaries set by society. There are allusions to Marilyn Monroe (in “Greenery,” unless I am reading too much into this), along with the mentions of beauty in association with intelligence (“Thelyphthoric”). How do you define femininity and feminism? How does your poetry define these terms?

I can only speak to my embodied lived experience. And I’m perhaps revealing my own identity through my allusions. Definitely, when I was coming of age I felt walls between being taken seriously as a thinking person and trying to be “hot”—again these are an adolescent’s problems, but ones I wanted to peek at again as an adult writer.

One of my absolute favorite poems in this collection is “Guilty,” an Ancient Grecian call back to modern-day guilt, and discovery. What does this poem mean to you? What is the influence here?

Ah, thank you! “Guilty” is a song title—a Britney B-side. I wanted to write about a feeling that was the impetus of a lot of this book: seeing yourself in a club bathroom. Every time I tried to write about sobriety (both as one of the morality play figures and also as something I wanted to achieve for myself) I found myself writing about alcohol, about drunkenness. There’s an ache for something sacred there, and for me drinking and sobriety had that in common: they (for me) both brought their own kind of elation and questioning.

“I used to think the line ‘I look so good on you’/ was ‘I left some good on you.’ I sang it wrong as/ this was a time before facts, before searching.” If I had to choose my favorite lines from any poem, I think these would be one of my top picks for sure. Self-discovery seems to be something big in this collection. It can almost be seen as a coming of age to a certain extent, although maybe not by traditional means. What were you thinking of when you wrote this poem?

Thank you! I like how it’s self-discovery by incorrect means, too. A time before facts, before searching, is another way perhaps to say before I googled every unknown. As a pregnant person right now, every single thought and question can be answered for me at pace. While I didn’t have too many years on the other side of the internet, I do remember it. Misremembered lyrics, unknown lyrics, there were mysteries that felt impossible to solve then.

I believe that Morality Play is one of those poetry collections that you can just read over and over again, picking up something different each read-through. As the writer of this book do you believe this to be true?

I know it’s true of my favorite books and a skill my heroes possess so I’m sure I was subconsciously reaching for that. There are so many ways to experience a book. I give a lot of readings and often hear it’s easier to enjoy a poetry reading—that element of live theater that allows us to readily metabolize speech patterns that don’t sound like an essay or a narrative. I’m a lyric poet at the end of the day—what can I say I like mystery!

Do you have any other upcoming publications that we should all know about? Any fun projects that you have been working on that you can share any of the details about?

Working on my third book at present, which will, fingers crossed, be my first earnest foray into form. I tend to write an entire book, erase it, and retry a few times. After that, I’ll keep some form of it, get my first readers to give me a heat read and I’ll take it from there. I love the idea of a sonnet book. I love when a poet who doesn’t always work in form tries their hand. Above all, I’m attracted to the confidence of any book entitled “poet’s last name – genitive apostrophe – SONNETS”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Samantha Zimmerman is an editor of Pine Hills Review and is an all-over-the-place poet with a passion for all things experimental and confessional. Her work has been featured in Sledgehammer Lit, Bullshit Lit, Discretionary Love Magazine, BarBar Lit, and The Afterpast Review. You can keep up with her on Twitter @samthezim.