After two years of teaching as a grad student with no training or oversight, I landed adjunct positions at two colleges in Philly. I was still a mediocre teacher, but I had a degree from a prestigious program and I had experience; colleges are so desperate for cheap labor they will take chances on anyone for a semester. College had been easy for me, so I never paid much attention to what my professors had done. It took me almost a decade to understand the challenges of students who were struggling just to stay afloat.

Because I had been a grade-obsessed student, I felt intense guilt about giving any grade worse than a B+ on an assignment. I often inflated grades because I didn’t have the courage of my convictions. Part of me knew it was unfair for freshmen to have their GPAs ruined by a class in which they were getting poor leadership and no coherent instruction. Part of me just didn’t want to deal with the confrontation, to become the bad guy. It was so important to me then that my students liked me (still my most frequent anxiety dream—being in front of the classroom and asking questions but no one is listening or even pretending to care, and the more I scream at them to show me respect, the more they laugh at me, and eventually I either storm out of the room or they walk out in protest). When I returned papers, I used to leave them on the desk at the front of the room for the students to pick up on their way out, and while they sorted through the pile, I sneaked away and hustled out of sight, like a coward. Once, a student who got a B- on an essay melted down in front of the room before I could escape, bawling about how she needed a 3.5 GPA to get into veterinary school, how mean I was to everyone, how stupid the class was in the first place. Confronted with such a raw display of emotion, I said nothing and waited until she collected herself enough to leave the room. She filed a complaint against me, but upon review the department determined that a B- had been an overly generous grade. I hadn’t discriminated; I had just set her up for failure by teaching nothing specific and grading based on loosely defined criteria.

Before grad school, a former professor had told me that my only job was to write, and never to let any other responsibilities get in the way. I followed his advice halfway, in that I didn’t take teaching seriously, but I also did very little writing. Now that I was an adjunct, teaching was no longer a thing that had happened to me accidentally, but rather a position I’d specifically applied for. I still didn’t know what I was doing, but I was trying. On the rare occasions when I gave students mediocre grades, I wrote very long notes, encouraging them, explaining how they could improve, justifying myself. One class period, I handed a C+ paper back to a student who was a nice guy but utterly unprepared for college. My note was nearly a page long, and arguably the most earnest thing I’ve ever written. I had spent the morning dreading giving him this paper.

His eyes widened, then he turned to his friend and punched him in the shoulder. “C+, bitch!” he shouted. They high-fived and left the room.

This memory is lodged so deeply in my mind it will be the last thing I ever think. I will be dying, hooked up to a cluster of tubes and machines, and surrounded by loved ones saying their final goodbyes. I will shout “C+, bitch!” before drawing my final breaths. They will puzzle over my meaning. Later, they’ll pretend I’d said something more profound.

I failed enough students that semester (12 out of 36) that I emailed my department chair to ask what a normal amount of failures is (His response: “It really depends on the quality of the students”). I felt intense guilt about failing them, especially once I learned about the strong correlation between failing freshman composition and dropping out of college, of student debt and low earnings potential and everything else. Now that I teach full-time at a large state university, most of my students are burdened with complicated backgrounds: low-income families, undocumented parents, disabilities, poor high school preparation. Big schools take in thousands of children every year, brag about their record class sizes, and then toss them into the deep end of the pool and see what happens. I am the only authority figure on campus who will know most of my students’ names during their first year, which means if they drop out, I am the only one here who will ever remember them. They get placed into one of 150 sections of composition based on the whims of an advisor, and then find out whether they’ll have someone like me now—an experienced, invested professor who knows what he’s doing—or someone like me from 2007—a frightened, unprepared guy who takes every mistake the students make as a personal attack.

This is what people want to talk to me about when they learn I’m an English professor:

- Books they hated in school

- The one big grammar rule they almost certainly misunderstand but cling to like a lifebuoy for some reason

- The various books they have at one time considered writing, but haven’t written

- Everything they think is wrong with lazy and entitled students these days

None of these are good conversations, obviously. People take great pride in being better than the generation after them, especially if they don’t know anything about that generation. Acquaintances assume I secretly hate the students, and they keep giving me prompts to invite me to trash them.

Listen: there are a lot of kids in college who aren’t prepared. There are a lot of kids who do stupid things, who write poorly, who have only the slimmest knowledge of history or literature or religion or civics. There are lots of kids who are getting drunk and high and missing deadlines, maybe not in that order. The number of shameless dead uncle and sick dog emails on deadline nights is consistent and incredible. Almost everyone is on their phones and their computers too much. In 2007, I would never have believed myself saying this, but I genuinely like these students, with their messiness and their drama and their irresponsibility. The whole point is for me to help them navigate a stressful, challenging time in their lives and give them the tools to come out on the other side a little better prepared, a little more open-minded, a little more skilled.

Some of us had the luxury of being annoying within the context of a system that basically made sense. You went to school and got a degree and maybe money was tight through your 20s, but eventually you were doing just fine and you could accumulate wealth. My students are acutely aware that they’ll be in debt for the rest of their lives. They’re aware that college is a bad bet, but it’s the only bet they know to make. They trust me to help them improve their odds just a little bit. So I’m going to go to cocktail parties and trash them for reaching out? What kind of person would that make me?

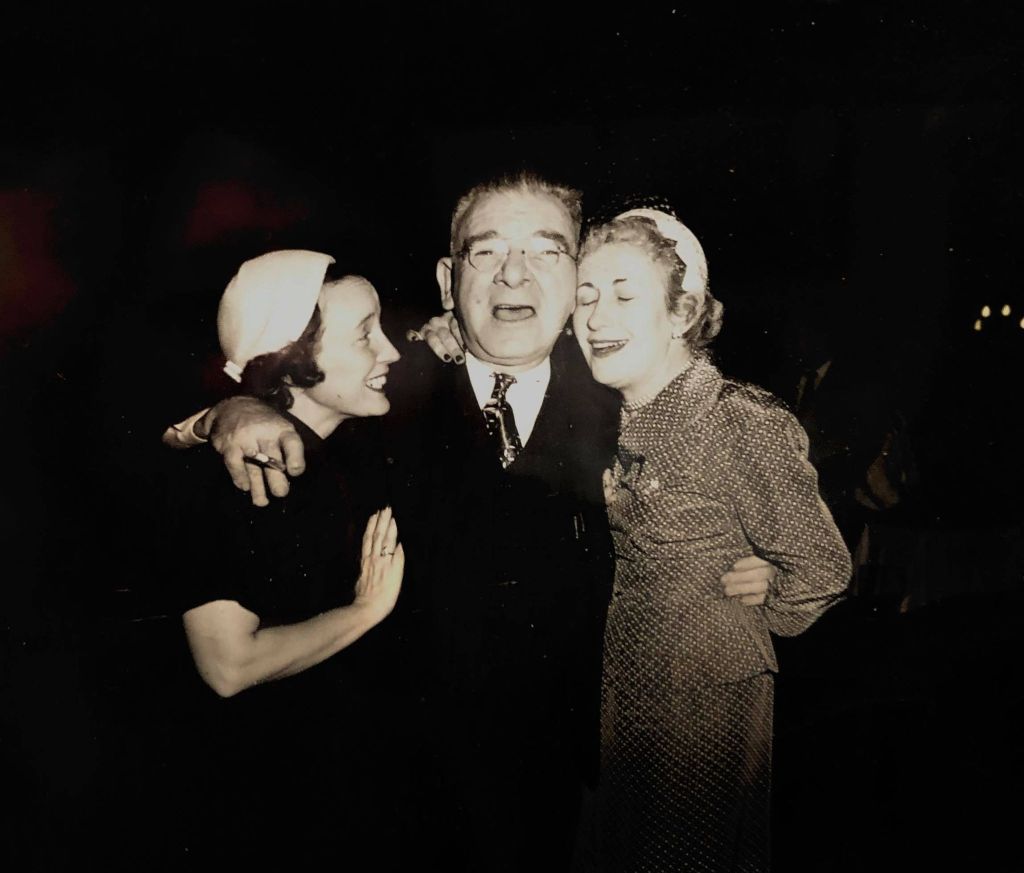

If I’m being honest here, I was exactly that kind of person when I started teaching. Now I’m some other kind of person, and if I’m writing about the most important thing that happened in 2007, I have to tell you that’s the year I got married. We went to San Francisco on our honeymoon. We went to Napa and drank wine. It was a beautiful time. We were so young we had no idea what we were doing. I look at the pictures and I still recognize both of us. We went up in a hot air balloon and from high above we looked down at a field of sundried tomatoes, and it was the reddest thing I’d ever seen. You’ve never seen something so red.

Tom McAllister is the author of the novels How to Be Safe and The Young Widower’s Handbook, as well as the memoir Bury Me in My Jersey. He is the nonfiction editor at Barrelhouse and co-host of the Book Fight! podcast. He lives in New Jersey and teaches at Temple University. Find him on Twitter @t_mcallister.

Image: “North by Northwest” by Anthony Burt