Terms of Endearment

My grandmother asked once,

“Why do you like this movie? It’s more

of a woman’s picture.” A rotary phone rings

on a stack of Prousts as my new husband fucks me

to “Gee Officer Krupke” on a mattress on the floor.

Six years older than Debra Winger’s character,

I don’t think I could manage being a quisling

in a maroon bathrobe cooking everyday Tex-Mex,

with child, not to mention three, sitting in a hot shower

patting the back of a baby with croup,

my husband off with the grad school girl

in tweed, stuck in Des Moines. By choice,

not by nature, I would be dead by now.

Before that, increasingly spiteful, contrite.

Yearly, phones become more cordless, the absence

of my wildness becomes deeper. My life orchestrated

by a sentimental Michael Gore score. I never thought

I’d start to need him, I say to myself, unwrapping

the pink tissue paper holding my rose-patterned brassiere.

Come to laugh. Come to cry. Come to Terms.

The poster promised. Like the Get Well Mommy cards

around my hospital bed or the orange light

of The King of the Whopper sign becoming brighter

as night wears on. The mission of advertising

is to validate feelings. Maybe I am more of a woman’s

picture in a mauve cloth dress on an overcast day,

the trade towers behind me, capped in fog.

“What’s so god-awful terrible about my little tumors?”

I ask. My grandmother says, “Oh God,” while laughing

at MacLaine’s “fan-fucking-tastic” line. Yearly,

things become more pronounced and more mundane.

We all get ecstatic, we all get ill. I never thought I’d start

to need anyone, I think, as I sit on the green astroturfed stairs

of the Cornhuskers’ Holiday Inn, watching children

play in the pool. One whips his hair, splashes,

then smacks his little brother. How quickly glee can turn

to tears. All of it a wailing cry outward or in, all of it to end

with a mascara-ed and violet eye-shadowed deathbed scene.

Years later, my grandmother confused by who I am.

Little Cathedral

I am not there but walking through her house—

possessions in plastic, strips of masking tape

bearing our names. I was left a little church

with a frosted bulb to light up inside. I used to wish

I had a Barbie to brush and dress up to lay down

in the path between the pews, blue-eyed gaze frozen.

I was left instead with dust in the hushed

sunlit house. Sitting on the floor to click the light

through the red and blue glazed plastic windows.

The house heavy with the death of her son found

hanged in the basement and my blind uncle who sat

with a frozen gaze, head back in a green chair,

radio crackling, pipe smoke rising around him. I am not there

but sleeping on the sunporch. A stack of cassettes, windows

wrapping the room to look out onto trees

and the cracked tar driveway. The realtor doesn’t think

it’s a tear-down—that there’s value in its age and character.

But lately the suburbs are cladded with McMansions.

My aunt shook her head at the strip malls going up

over farmland—concrete cathedrals—Oscos closing

for enormous, sun-drenched organic markets.

A Jenny Jones episode showed queens hollering

at one another. My aunt said she didn’t understand

why gays were that way. I don’t mean to paint her that way,

but it sticks. I was furious inside and I still don’t know

how to articulate it. I sat with anger under the ornate dome

in the Baha’i House of Worship. The vastness of religion

and its disturbingly enlightened tribes. When it was hot

in the heat wave, we sat near the sweating window unit

and fanned ourselves with doll magazines. My sister and I

trekked to the mall where she worked at the Gap. The cold,

clean bright white store stacked with jeans and plaids and khakis.

The scents of Grass and Dream perfumes. Today she visits me

in Jersey and we venture out in snow to the mall. We are still

browsing with more layers of years over us. Twenty-three years ago

we saw Clueless at Old Orchard. Her boyfriend at the time

said it made him want to be in high school again. I doubt I’ll ever

end up rising enthusiastically to mornings of picking outfits

from an electric rotating closet rack. I lacked human interaction

and listened to songs like “In the House of Stone and Light.”

One rainy evening on the sunporch, the radio DJ announced

a new track from Michael Jackson called “You Are Not Alone.”

The music only took me so far. Soon I would leave that life.

I am leaving the house to stand in the driveway

to look up at the tree-reflected window

I’ll never look out again. I see my aunt smiling

in her glasses and denim skirt. People are always arguing

over objects. I rise to the day. I unwrap the church

from dust-scented tissue paper and I clear a spot on the shelf.

Becoming a Piece of Work is Man

My former self, drunken night out

in the club on the Scotland high school

drama field trip. Someone dropped a bottle

of beer on the dancefloor. We laughed

under the mirrorball over the shards.

Summer was open to me—I ran fields—

so green, weren’t they? The wind whipped up

my blond hair at the top of hills.

We snapped photos on black & white

Kodak disposables. I stood dramatically

against the blue sky in tight dark denim

with a vintage baby blue Adidas track jacket

and baby blue Nike high-tops. The pictures suggest

glib naiveté and blank melancholy. I cried

reading the end of Catcher in the Rye

on the plane ride over, night clouds

out the window. I went to Waterstones,

asked if they had Becoming a Man

and I was led to the gay section.

“Why do you want to read that?”

Asked a former friend. At dusk,

out the windows on the double-decker—

the curving streets alive. I began to read.

In the countryside, we skipped through heather

like idiots. In a black box theater:

Hair. The sweaty cast half-nude, writhing, belting out

Facing a dying nation. John and my arm

around his hardened shoulder

as he helped drunken me into his bedroom.

His breath of cider. I am thinking about John’s eyes.

I caught a too sweet, too brief moment

atop a cliff listening to Kate Bush scale

“Wuthering Heights” on my Walkman.

He wanted something we couldn’t speak.

Now he is grinning, sunglassed in digital

with his husband—an added layer

of the could-have-been. The stirred-up

feelings first reading the Monette.

The handsome model in black & white

on the cover, standing dramatically

against the sky. His Adam’s apple.

Streams of words all around

the flitting ruins of castles.

May you never lose that joy—

that breathtaking sense of possibility.

How dare they try to end this beauty?

But it’s hard to go back to that,

hard to replicate. Scaling cliffs

without knee pain. I know I’d be

saddened to return twenty years back

to the ache. And what would I have done

anyway? Performative writhing.

A pang when I find my stub to Hair.

Jeffery Berg’s poems have appeared in journals such as Impossible Archetype, Other People’s Flowers, Punch Drunk Press, El Balazo Press, GlitterMOB, the Leveler, and Court Green. He received an M.F.A. from NYU. A Virginia Center of the Creative Arts fellow, Jeffery lives in Jersey City and blogs at jdbrecords.

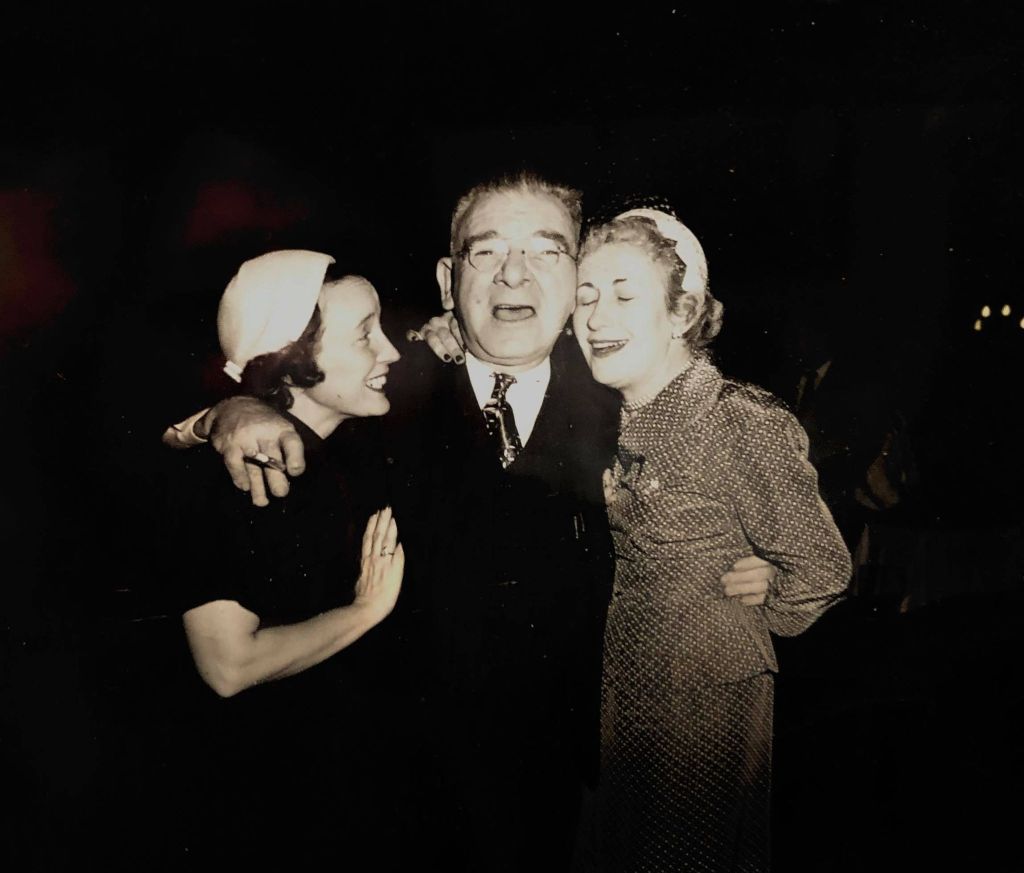

Image: “Painting Astoria” from Facebook Marketplace