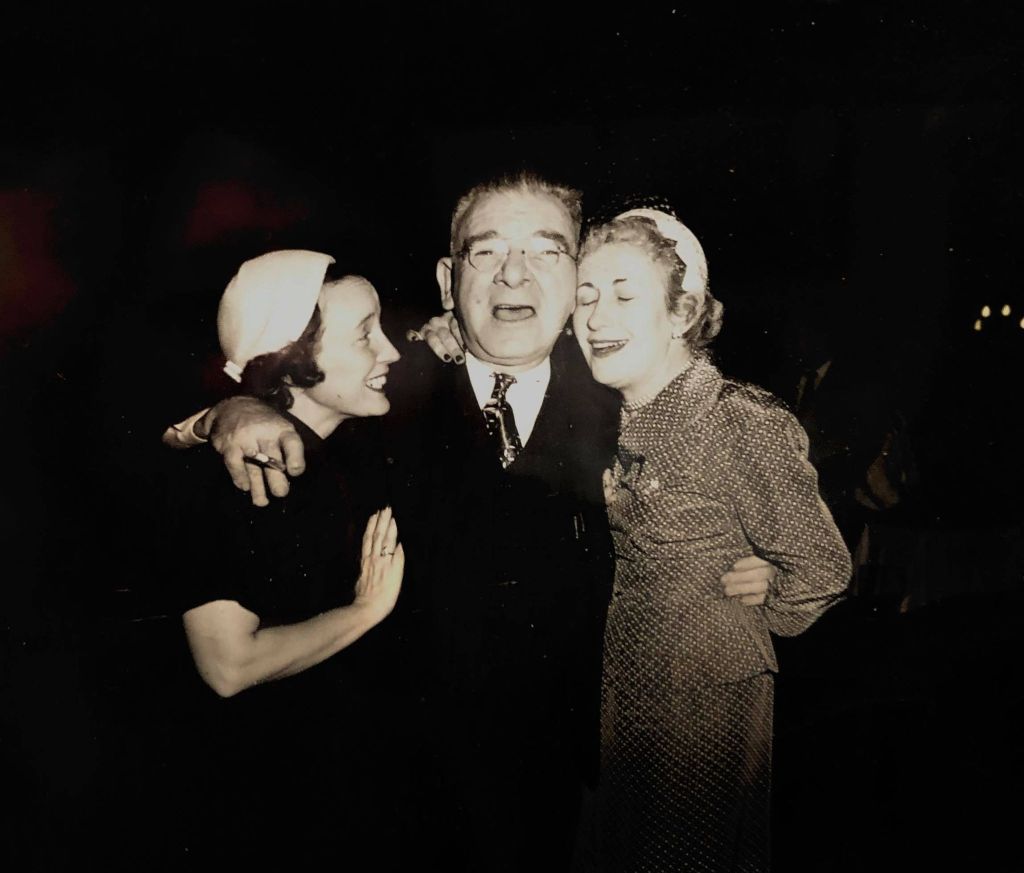

Writer, editor, and adventurer James H. Duncan gathers audiences in a warm embrace with compelling short stories and poems. His most recent book, Both Ways Home, includes poems and stories that explore his beloved hometowns of Albany, New York, and San Antonio, Texas. Kevin Ridgeway, the author of Invasion of the Shadow People, writes Both Ways Home is a “vibrant, heartfelt collection that beautifully connects two hometowns,” that “masterfully brings to life the people and places dear to him.” Duncan’s work has appeared in a number of literary journals and has been nominated for awards such as the Pushcart Prize. In this interview, we talk about the emotional impact the places we grew up have on us, what it means to be a dreamer, and the concept of an infinite reality.

Your website mentions that you consider yourself to be a dreamer or someone “always hopeful of romance and adventure.” I can see this sentiment throughout your work, particularly in “Turn the Lantern Low,” from Both Ways Home, in which you reference a particular dream:

I dream of my father

and of my sister and the long journey

it took to get from my childhood to my grave

and it is there on that hillside where

my final living breath

will be clear

and raw

and free

These words are beautifully crafted, and while death tends to be a topic not many people feel comfortable talking about, you manage to view this more existential topic in a way that feels hopeful. I wonder, have you always been able to look at the more significant unknowns of life in a way that feels less threatening, and more gentle? Do you owe your idealism to your special abilities as a self-proclaimed dreamer?

That poem came from a drive my father, sister, and I took in western Texas, out in the mountains near Big Bend at night. I spotted a quiet little ranch all alone that looked so peaceful. Even as a teenager I kept thinking how nice it would be to take my final breath in a place like that, with beautiful vistas on a calm summer evening.

Morbid, perhaps, but I’ve always had a sense that the clock is ticking for us all, even at a young age. People I cared about passed on in a rhythmical stream, every few years another funeral, another loss, distant family members gathering again until the next one comes around. It takes on a sense of inevitability that doesn’t necessarily make it less scary, but it inspired a sense of adventure and risk-taking when I was young, leaping into cars and leaving jobs and worlds behind and just going. Even if mistakes were made along the way, it felt better than staying put. I wanted to spend some time living a life worth writing about.

And when I travel, I often dream about the many lives unlived, the different choices I made that could have had a dozen other outcomes. Sometimes when passing through someplace new I’ll think, “What would life look like if I lived here instead? Where would I work? In that hotel maybe? Or that bar? Who would I meet? Would I be happy? Depressed? Would I be a fundamentally different person?” You start doing that everywhere you go and you’ll see the infinite possibilities of the human experience, and it’s all worth writing and dreaming about.

I sometimes become too nostalgic for these places and daydreams and I concoct almost cinematic lives unlived, places that feel gentler, wistful, and peaceful. It’s sort of nice to imagine those things even if you already enjoy the life you’re living, and it helps keep the more frightening aspects of life and death at bay.

The love you have for both of your hometowns, Albany and San Antonio, is refreshing to read about. People are always talking about wanting to leave the places they grew up, never taking the time to appreciate the good aspects of what is familiar. While I find myself thinking about the day I too, move to a new city, poems including “Albany” and “Ode to Madison Avenue at 6:15 pm” remind me to focus on the smaller details that make the world around me right now something to be treasured. I guess my question would be: what are the small aspects of your day-to-day life now that help to keep you grounded and present? Is there a certain ritual or activity that guides you in maintaining a healthy perspective when things get tough?

I was the type of person who wanted to get away from Albany as soon as I could when I was young. But after living in a lot of different places around the country and coming home to Albany years later, I realized I had a lot to re-learn about the area. I was familiar with Albany, but I felt a little like a stranger too. A lot had changed. Most friends had moved. Favorite bars, restaurants, and even childhood landmarks like Hoffman’s Playland were all gone.

So I took it upon myself to explore my hometown and try as many “new” things as possible. Where have I never been? What have I never done? A show at The Egg, a beer at a new brewery, an afternoon in a park I’d driven by hundreds of times but never walked through. I began seeking out the many different bookstores in the area and cataloging my journey to each (leading to my blog, The Bookshop Hunter) and there are dozens and dozens within an hour of Pine Hills. We live in an area that is much richer and more diverse in experiences than one might think, and I always try to consider what aspect of the area I haven’t yet experienced.

It helps keep life fresh and helps me appreciate a place I once yearned to escape.

You are a well-traveled individual who has explored multiple regions across the United States. Your work feels as though you are now taking readers on a figurative journey in which you reflect on life and all the places you’ve been. For those of us who are less well-traveled, and I include myself here, is there a certain message you have for someone who wants to go on their own personal journey through life?

When writing Both Ways Home, I tried to keep in mind the many cross-country journeys I took traveling back and forth to each hometown. The cross-country road trips, the motels, the strange roads, and missed exits. Going on those adventures is something I’d recommend to anyone at any age, but especially if you’re young: get in a car and drive for days or even weeks at a time. See the country away from the highway, away from airports, away from commercial strips with the same restaurants and big box stores. See something offbeat and strange while you can. I’m very grateful I took some chances in my 20s to get out on the road, even if a lot of my choices were objectively unwise and short-sighted.

For example, I worked for the Times Union newspaper here in Albany after college and I loved it, but I also craved new horizons and had a fear of getting into a rut so early in life, so I quit, sold everything I had, and drove west. Which resulted in me spending most of my 20s on the edge of poverty. But I met a lot of fascinating people and saw a lot of amazing things, and if you’re planning on doing anything in the arts, I highly recommend throwing a little caution to the wind and exploring the world while you’re young.

If you’re going to have anything worthwhile to say, you need to fill that cistern of inspiration within you with diverse life experiences. Mistakes are inevitable, whether you stay or go, so why not go and try something new?

Do you recommend using poetry or art as a means to properly introspect one’s experiences?

Absolutely, and poetry has always felt like the most honest way to scrutinize my life experiences. I love writing fiction, whether semi-autobiographical or totally new, but that requires so many levels of consideration: crafting an arc, guiding a reader along, and maintaining the right balance of description, exposition, dialogue, action, etc. Not that those things don’t come into play with poetry at times, but poetry feels much more stripped down, getting rid of unnecessary layers and keeping what matters most. It makes it easier to explore a moment, a scene, a feeling, and what was important about that snapshot in time. You can write them faster, read them faster, and they can hit you just as hard as any 500-page novel if done well.

In pieces such as “strange gods of the prairie” and “Afternoons in Bulverde,” you pay close attention to the colors around you, noting how they impact you emotionally. When referring to your time in San Antonio, you talk about the orange horizons, the hard yellow dirt, glowing insects, and the pale blue sky. Does this association of colors serve as a driving force for you creatively? I’m curious if you are interested in art or painting outside of writing.

I once lucked into a job at an art magazine in NYC where they sent me on assignment to artist studios in Brooklyn or Beacon, painting events out on Long Island, and galleries and museums throughout the northeast. I learned a lot about painting, art, color composition, forms, and techniques, and while I’m not a great painter myself, I enjoy it whenever I have time. And it helped me keep an eye out for that sort of thing when I traveled and wrote. Every region has its own unique palette.

The San Antonio area has a dusty array of earth tones (sandy browns and olive/sage greens) but that’s accentuated by these wonderful pops of fiesta colors, the pink homes, rainbow-colored patio umbrellas along the River Walk cafes, and spectacular sunsets. Albany always struck me as a rather gray city growing up, but that was just a connotative memory based on the marble expanse of the Capital Plaza. In truth, it’s an incredibly lush city, with colors that change with the seasons, the opulent reds, yellows, and whites of tulip season in Washington Park, the rich greens and blues of summer, the fiery oranges and reds of autumn that meld into a hazy purple in the right light. Living in the Hudson Valley is quite a luxury. We get so many different seasonal colors and all of them inspire.

In a number of your writings, specifically in “The Majestic,” I get an overarching message that is along the lines of “life goes on,” or that life does not stop giving a person opportunities:

but when we rise for the final applause

we realize, each quietly to ourselves,

that all things must occur along all timelines,

certainties in abundance

though I hold out hope that somewhere

along one of those infinite strands of existence

the play goes on in a life unwritten

I think you may be driving home that there is a comfort to be found in the idea of an infinite reality. With this mindset, we can also create and find our own meanings. Would I be correct in suggesting this, or did you have a different message in mind?

You are correct indeed, and it’s always been something I’ve kept in the forefront of my mind.

Even as I experience something, say going to the Palace Theater for a show or a movie, I catch myself wondering what it would be like there in the 1950s, 1920s, or 1880s. I wonder how many other people have cycled through those seats, lived in our apartments, and drank in the bars we frequent. It sometimes feels like life is a series of people rotating through the same rooms and spaces, living whole worlds we’ll never know. And we are also living lives those people will never know, instilling our own meaning into our day-to-day, year-to-year. You start thinking about all of that happening to all of us all over the world, all through the years, and life starts to feel infinite, a vast sea of experiences happening all at once. I find that kind of exciting, and fun thing to daydream about from time to time.

Two of your poems, “How to Watch John Ashbery Read Poetry” and “Umbra,” were published here in Pine Hills Review. I can imagine that seeing so much of your work published in a number of journals and publications helps to solidify an author’s sense of their abilities. In your case, would you say this has also been your experience? Does the official publishing of an original piece continue to excite you for what’s to come in your career, or is there any pressure to quickly get another work out there?

Having a piece published is always exciting because it means someone somewhere likes your work. Though I’d caution writers to equate publication with “success” as there are some publications that will take almost anything, and others that will take almost nothing, no matter how talented you may be, unless you happen to “be” someone or know someone. So while being published is validating and exciting, I always advise you to keep humble, keep your standards up, and take rejections with a grain of salt. Rejections may have nothing to do with how good you are. It might be the wrong publication, the wrong editor, the wrong piece, or the wrong time.

I submit far less often in recent years, and I don’t always feel the pressure to do so. I send work out when the poems tumble out of me, with no pressure at all. I’ve been focusing more on novels and submitting those to agents, but when I do have a poem or story accepted somewhere, it’s still very encouraging. I’ve grown a lot since I started writing and the fact that pieces are still accepted now and then means I’m growing in the right direction.

The key is to not stop growing, never box yourself in with a certain style or structure, and always look for new ways to say the things you want to say. If the acceptances come along, all the better. If not, keep trying, and keep growing.

Throughout your book, I found myself relating to the ways in which you connect to your own humanity. You explain how the morning light and the pain in your heart ultimately remind you that you are alive. I’ve always clung to the idea that both the good and bad can serve an important role in one’s survival. Would you say there was a certain moment in time in which you too realized this, or is it an ongoing mental process?

I agree that good and bad can serve an important role, both in survival and the artistic process. I didn’t personally really know what I wanted to say or even how to properly say it until I experienced a period of deep loss and trauma in my mid-20s, the kind that uproots you and sends your life in a completely different direction overnight. Not that anyone wants to experience that kind of great pain, but I believe that desperate times can sow the most fertile fields of creative inspiration. You feel life crumbling all around and you grasp for the one thing you still control your creative expression. Trying to make sense of our worst days through art can lead to surprising periods of creativity.

The joke that we write poetry as free therapy is not too far from the truth. But it’s important not to wallow in those dark times for too long. Inspect them, understand them, write about them, and use them to move forward, and expand outward. Use those introspective tools you gained and explore what else is happening in the greater world, the many shades of human existence. The ability to write about what’s happening around you (the universal) and connect it to what you’ve learned about your own inner world, feelings, and experiences (the personal), will allow you to create balanced, insightful poetry with greater depth, breadth, meaning, and accessibility.

Jasmine Bates is a passionate writer and creative. She graduated from The College of Saint Rose in December 2022 with a Bachelor’s Degree in English. She is excited to continue forward with her writing career.