During the pandemic, I lived in a small studio apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Before the lockdown, my life was relatively normal. I was a nanny during the week, and I enjoyed the carefree lifestyle of a young twenty-something on the weekends—traveling, reading, writing, thrifting, and wandering around the city. Like everyone else, my life changed when New York City went on pause in March 2020. Suddenly I was unemployed and stuck (for months) in my 400-square-foot apartment while my partner, an intensive care unit nurse, spent her days on the front lines working tirelessly to save lives.

My story is not unique. It’s not even particularly sad or interesting. But there is something universal about it. That is because, for many of us during the pandemic, life as we knew it was forever altered, and during those two years of uncertainty, we recognized the fragility of life and discovered new ways of living and connecting. From Zoom to the 7 o’clock cheer, we persisted in the only way we knew how during this period of isolation: we persisted through community.

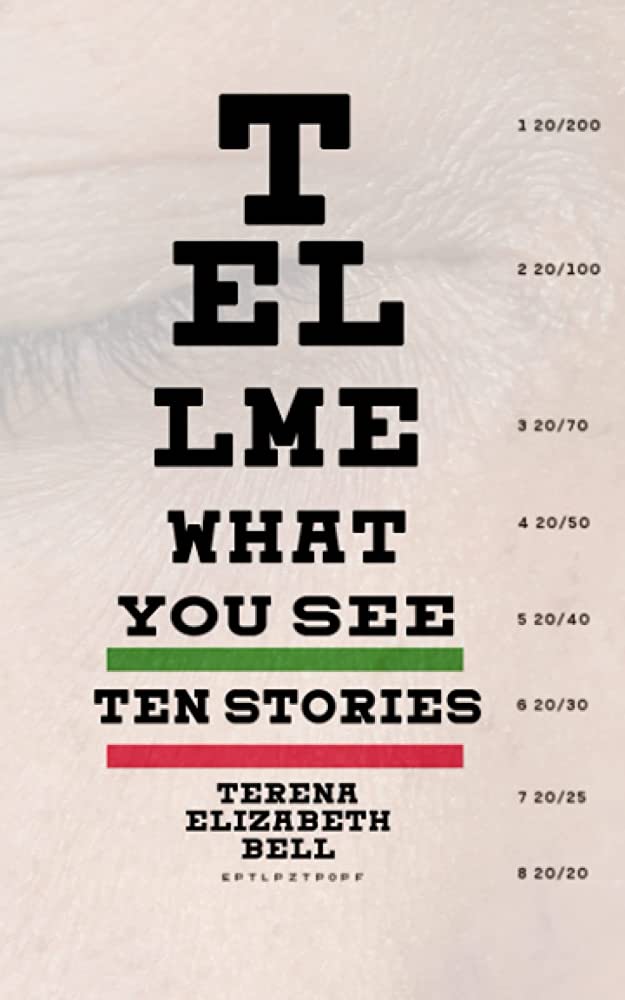

In her short story collection Tell Me What You See, Terena Elizabeth Bell unpacks some of these complicated experiences, particularly of those living in New York City during lockdown and political polarization. Her language and experimentation captures the feeling of life on pause, of time stretching and escaping. It captures the unpredictability of existence in a post-pandemic world. While reading, I went through the full range of emotions. These stories are demanding. They confront the reader with the weight of past loss and the fear of an unknown future, but for me, despite their challenging nature, the pieces were deeply therapeutic. In this interview, we discuss transplanted Southerners, ADHD and writing, and Thornton Wilder.

“The Fifth Fear” is broken up into five sections called ‘Tomes” and hinges between realism and dystopian surrealism. You take familiar images and locations—The Statue of Liberty, the Hudson River, the M17 bus, the Upper West Side—and juxtapose them with elements of science fiction, such as “the portal.” Why did you decide to keep these familiar elements in the narrative?

Each writer who’s reviewed my book has had a different idea of what “The Fifth Fear” is about. One thought it was a commentary on increasing tech use in society, another said the anxiety of being human; I had a beta reader ask if it was about turning 30 and leaving youth behind. None of those are it, but there’s no harm in letting readers think what they want. There rarely is a “wrong” in literature—just different interpretations, which are valid if you can point to the text and prove them. When something I’ve written can reflect so many meanings, I know as a writer, I’ve done a good job; I’ve created something so wonderfully complex that English majors can vehemently disagree about it in class.

To be clear, I wrote “The Fifth Fear” about the coronavirus lockdown in New York City. The “portal” in the story (a Stargate-type contraption between Manhattan and the Hudson) symbolizes the moment all New Yorkers went through when we moved from life before the pandemic into New York on Pause, a “two-week” period where Governor Cuomo asked all residents to stay inside. So the reason these landmarks are there is because the story is set in New York.

Even when the city was no longer the city, those icons were still there. Think of it as the Statue of Liberty arm sticking out of the sand on Planet of the Apes. It’s a trope, but nothing symbolizes New York City more. And the idea of the Statue of Liberty crying, like physically bending over and shedding tears, well, that’s an image of the deep, profound grief permeating the city at that time that I thought non–New Yorkers would understand.

The footnotes in “The Fifth Fear” clue the reader in on insights about the world in which the narrator and her friend Amanda live. The fifth footnote in the second section, “Second Tome,” reads—“The flyers promise you will not get old. There’s not time to grow old in the portal, the portal is built to last two weeks, but one week past the portal is one month at the portal is one year for New York on Pause, and to quote Douglas Merritte, ‘Isn’t that just like a dream: a broken promise? And the loss of this promise, the mutilation of id itself?’” There are obvious parallels between this story and the lockdown in New York City in March 2020. How did you negotiate facts from fiction when writing these stories?

Fiction is fiction: a substantial portion must deviate from life to be substantially ‘made up,’ but every short story contains some element of truth. Bus ads in New York (called “the flyers” here) are horrible. They always make ostentatious claims or try to be cute in really bad ways. So saying these ads make failed promises (like quarantine will only last two weeks) is a fact. It’s in this fictional story because ads are part of the backdrop of New York.

Now, do any of these real-life ads say “LOSE YOUR ONE LIFE,” as they do in the story? No. That’s where fiction comes in.

That makes sense! The “Third Tome” completely abandons traditional syntax, spacing, and punctuation, which puts the reader into a hypnotic disorientation that mimics the time warp outline in the previous sections. This Bergsonian approach to time and duration is particularly interesting to me as it illuminates the reality of a continually extended quarantine and the feeling of time stretching during a lockdown. With that being said, this is the shortest section of text.

“The Fifth Fear” came from a dream, so some of the time-twisting is my effort to sustain that dream-like ethos. Most of it is because quarantine really whacked with time.

Now, in Kentucky, where I’m originally from, my parents and others were able to drive around and still went to the grocery and such. But here in New York in the early days, we did not leave our homes—not even for a walk. When you are in a single room, completely by yourself, every hour of the day, multiple days on end without even opening your window—something certain neighborhoods were advised against—there is no sense of time. Time does not exist. That’s how we get lines like “one minute past the portal is one hour at the portal is one day”—because there was no difference between a day and a minute.

There’s only so long you can write like that before it messes with your mind. I have [an] attention deficit, which means I hyperfocus when I’m writing. I often take on the emotional burden of my characters in the way actors do method acting, except I don’t mean to. It’s just my ADHD. When I’m really in the groove, I can sit there for hours, so locked in the story I don’t even remember to eat.

I wrote this particular passage in the laptop room at the New York Society Library, and when I got up to take a break, I was thinking like it. Instead of hyper-focusing on a character, my mind locked in on the syntax (“one minute past the portal is one hour at the portal” buh bah bum). I couldn’t quit thinking like it. I took a break to call my mother and was even talking like the story. She told me whatever I was writing was done, that it was time to stop. And she was right. I had a headache so bad that two years after writing that passage, I still remember it. It wasn’t my mental health per se (ADHD is a learning disability) more so I just couldn’t take it anymore. And if I couldn’t take it, the reader couldn’t either.

In the “Fourth Tome,” you use scientific terms—quantum foam, wormholes, a reference to late scientist Stephen Hawking, and of course, the portal. So, what is the portal? Is it life, death, time expanding and escaping, or something else?

The portal is New York on Pause.

I can relate. I lived in New York City during the entirety of the pandemic, and “#CoronaLife” really captures what it was like to live there during lockdown—the fear, the apathy, the millions of missed calls, the panic from friends and family (and that one person who you talked to for ten minutes at a house party in 2009) and, lest we forget, the Trader Joe’s lines. COVID-19 is not an easy topic to write about directly, but in this section, you use text messages to convey a narrative, which makes the subject approachable and unique. Did you source this section from real text messages?

It didn’t start with a text, but rather a Twitter direct message conversation between me and the wife of a high school friend. “#CoronaLife” focuses on the difference in attitudes toward covid in rural Kentucky and New York City: My friend’s wife—as well as her inspired character, April—epitomized Kentucky’s fuck-y’all-I-ain’t-wearing-no-mask attitude. My friend’s wife literally didn’t care if anybody died. Her concerns were purely economic. This was after Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear had placed minor indoor seating restrictions on restaurants because the Commonwealth’s rates were on the rise. So she tweeted about how “King Andy” wanted us to all be poor and how covid didn’t kill anyone—she specifically called the disease’s effect on children a “lie.” I DM’d in that early-pandemic foolishness of hoping for intelligent debate. Let’s just say there was none to be had, and I blocked her.

Now, this, unfortunately wasn’t the only conversation I had with people back home like this, but she was the only one who was unhinged. So when I went to sleep that night, I had this dream that texts and tweets from all these people were attacking me, just flying in from the right and left sides. They all said the exact same thing, something she had said in DM’s: Just because you live in New York doesn’t make you special. Who are you to tell me what to do?

When I woke up, I thought that’s a story, and I knew this was the end: a main character in the city who’s just been through what actual military veterans compared to war, and here this character is trying to warn her loved ones so she can save their lives—then they just beat the living shit out of her for it.

So did this story come from an actual text message? I stand by my detestation of all things auto-fiction, but sort of, maybe, yeah.

As a fellow Southern ex-pat, I can relate to the idea of well-meaning but ill-informed family members and childhood friends trying to advise you on how to approach the pandemic. Do you have any advice for those of us who are still working through these relationships post-pandemic?

They mean well. They really do. And by this, I mean the ones who are accidental dumbasses. Now, I’m answering this a bit more loosely because you’re also a Southerner, so I know you know what I mean. Trying to explain for non-Southerners who may be reading, though, the rural South is replete with some of the sweetest humans on earth who are far more educated than my neighbors in New York would like to think. But they tend not to be well-traveled. They’re often widely read, and highly versed in American and European history, but when it comes to the understanding that not everything in the US operates just like where they’re from, well, there’s a stopgap. The vast majority of people where I grew up have never been to the city—nor do they care to visit. It doesn’t make them bad or narrow-minded, as many might accuse. Their lack of travel often stems from either poverty or joyous contentment with where they live. In order to make up for their gap in cross-cultural knowledge, they do the best they can with what little bit they do know and try to show their love nonetheless.

During the pandemic, I think a lot of us—Southern or not—lost multiple relationships. This, I’m afraid, is where the on-purpose dumbasses come in: people who really didn’t care about other people, whether we lived or died, who knew exactly what they were doing from a place of evil self. Those are the ones I got shed of, not the ones who made mistakes and were unhelpful despite the fact they tried, but the ones who regarded an entire city of dying people as if we were fit to die.

These are two widely different groups. Their behavior may look the same from the outside because our overly-reactive society often intentionally perceives ignorance and hate as the same. But the people who meant well? Forgive them. Just forgive them. And run like hell from the ones who didn’t.

The title piece, “Tell Me What You See,” explores the idea that even medical professionals are unaware of their blind spots at times. How did you balance this narrative in a time where misinformation abounds and medical distrust is at an all-time high?

You know, I wasn’t thinking about medical distrust at all, but I can definitely see how it fits. I just set the story in an eye doctor’s office because that’s where an eye chart is, and I knew I wanted to build the story around the Snellen.

This collection of stories confronts a lot of dualities—seeing and not seeing, personal freedom and totalitarian government, time and duration, science and misinformation, power and fear—all centralized in the context of one crisis or another. What is it that you hope your reader takes away from these stories?

The truth: everything we went through as New Yorkers and that January 6th was wrong. I want people who didn’t live in the city at that time, who maybe weren’t even born yet, to be able to pick up this book and understand it. I wanted to show the rest of the world what I see.

This collection is a real smorgasbord of artistic expression as you use emotionally evocative visual images in stories like “New York 2020” and “Tell Me What You See,” as well as some more contemporary references through memes and text post-scripts in “#CoronaLife.”

Are there any authors or artists who have influenced your approach to writing?

On influences, I think writers are on some level shaped by everyone they’ve read—even bad books teach us what not to do. I read a lot of Thornton Wilder as a child. There was one summer I read Our Town front to back every day.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Samantha Ryan (editor; she/her) recently graduated from The College of Saint Rose and is a former managing editor of Pine Hills Review. She enjoys reading and creative writing. You can keep up with her on Instagram at @cutpapershadow.