The only years I can remember are named.

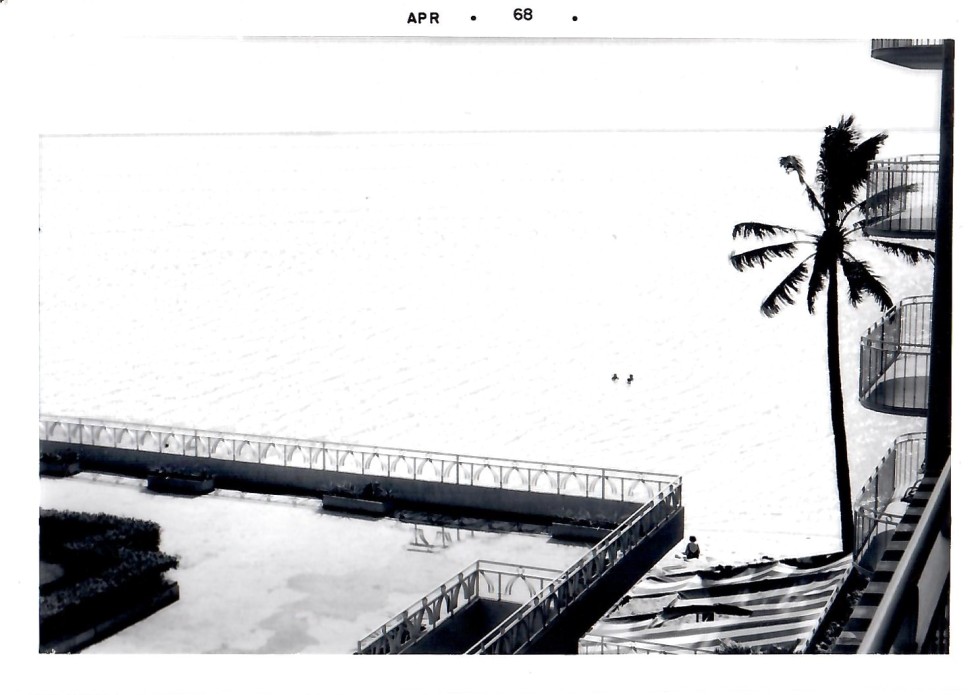

So far, 1970 has been Celia. It’s the year I decide to call my brother, Jonnie, for the first time. Jonnie left for Mexico in ’57, when Hurricane Carrie lasted for three weeks over the Atlantic. But the more storms I track and study, the more seasons I live through, the more storms become nameless during these seasons just known as “Summer.” It’s impossible to separate out summers from unnamed years.

For a few days, we’ve been tracking the development of a topical depression over the gulf. Its initial trajectory was easterly, forced to stay over the gulf because of the atmospheric pressure over Texas left behind by Celia. But our forecasts have shifted; the storm is strengthening.

The depression hit the winds circulating over Mexico. We’ve named it Ella, and Ella is already a category 1 leaving the Yucatán.

The directives set forth by our new director at work prohibit international calls; he cited the cost. So, I left the center and went home to call my brother. The number was from an official who had a friend who drank with Jonnie at the bar of a hotel he lived in, had been living. I’ve been sitting on the number for a year or so. I don’t know why it’s taken me so long to call him.

The phone rings. I watch one of my wife’s friends draw from her cigarette. The baby shower didn’t notice me.

The first ring: Mom, Dad, and I watch Jonnie and Gabrielle walk through the gate and disappear in the mess of anonymous passengers getting ready to board their plane meant for Tampico or Tulum or Tamaihua. We wave and wave goodbye.

My wife’s friends shout over the baby’s name. Each suggestion better than the mother’s. Annette takes biscuits out of the oven. And nods. I nod back.

The second ring: Jonnie runs up the stairs and I follow him to his room where we play with our plastic soldiers. We station troops along his bed frame, his dresser, and position platoons on the floor around bed legs. The battle begins: Good versus Evil—always my battalion of men, and will have no survivors. He shoots my soldiers with a rubber band. He loops another around his thumb and index as he runs over to the dresser and knocks down my soldiers he missed. I shout or cry something. I smell the radiator—always a few degrees away from engulfing the house in flames.

Each pause on the line, a chance for Jonnie to run across his room and pick up. Each ring is a chance for Jonnie to respond, his voice untouched by time. He doesn’t hang up when he hears my voice. Missed you, how Jonnie never said much like that growing up. I always read into the types of questions he asked; the more we talked about sports, the more I knew he missed me. Maybe the silence has been good for us. Missed you, too, how are you? I don’t mention the time apart—it hangs between us like a dancer waiting to split the couple during their tango. Some things never change, he says. How are you doing, Jonnie, how are you? I ask. I ask again, and again. He says, Life’s been—

The phone ring interrupts our conversation. His voice stalls like an engine out of gas. I ask him about the weather, about summer. I want to tell him about the storm, instead I tell him about Celia, how it bore right through Mom and Dad’s. I want to make him worry for never calling, checking in on me or them. But I tell him they’re fine. They were able to get out in time, they’re going to live with me since there’s nowhere left back in Galveston. He doesn’t say anything and the line rings again.

The ring draws a long breath. Pick up. Pick up, I need to warn him about Ella.

The crockpot lid rattles; Annette’s chili simmers on high. All the ladies place an open hand on the pregnant belly. As if Sunday worship, they rejoice when they feel a kick.

Over the years, at the center, we’ve improved our models tenfold. Our models are more accurate. We’re more precise with our predictions where hurricanes will hit. We’ve narrowed down probability-based impact zones. We have a better grasp of rapid intensification and the conditions to look for. Year over year, although the storms develop and evolve at an astronomical rate, so too, does our data and how we analyze it. But after a big storm, even if it’s not the storm that kills people; if it’s the rain or the flooding, winds and building damage, or a lack of government response, there’s not enough rain to also wash away the guilt. At the center, I think most of us feel that way. It drives us. It drives us to keep pace with the hurricanes. My first director, he used to have this saying I still repeat to myself, Today, let me lie down and bleed awhile and tomorrow, I’ll rise to fight again. Forecasting’s like boxing, just a chance to recalibrate and prepare for the next round.

The phone rings and Jonnie knocks out Harry Morton—who’d been bullying me that year. Jonnie stands over Harry’s shriveled body, tells him to leave me alone. It’s after school and the grass stains smell bittersweet against my scabbed-over elbow. Our classmates huddle around us; grabbing Jonnie’s biceps, re-enacting the fight, throwing pretend hands, they chant: pop, pop, one-two, one-two. Maybe my older brother’s folklore began that day. His mythos wafting behind him.

I wait for the next ring to interrupt me.

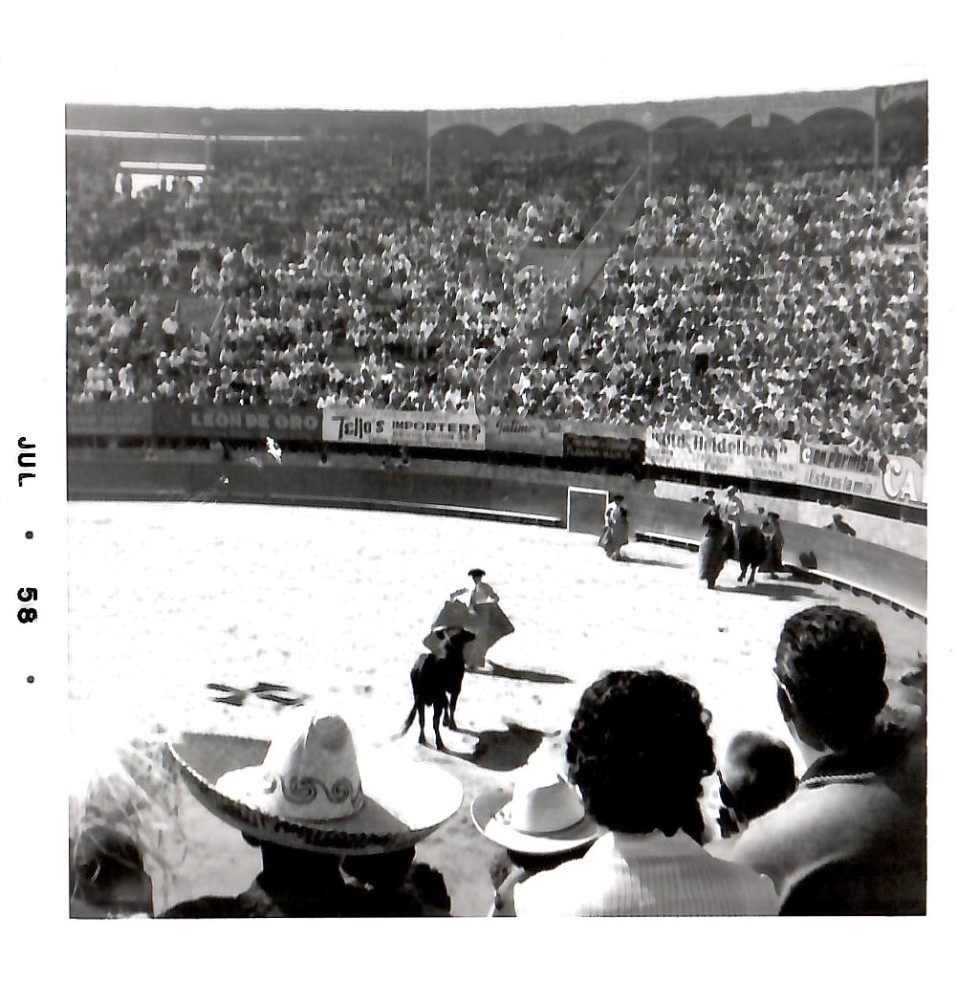

He’s probably watching Ella approach right now, through an open window; unchanged from sixteen-year-old Jonnie, who always had enough invincibility to actually believe it. He’s watching Ella barrel towards him with nothing except the shirt of his chest to protect him like a bullfighter—mano y toro y huracán—although Dad always made sure we were as far away from windows as possible. Dad made sure we never stood by doorways or under the valleys in our roof in case the rain, with the wind, would get under the flashing and weaken the roof until it collapsed. Dad was overly cautious, but that’s what he demanded of Jonnie and I. He saw the fallibility of man every time we were asked to evacuate and returned to those who didn’t leave missing. Dad always said, You’re irreplaceable.

The next ring doesn’t come.

Annette’s setting the table, so I hang up and help.

Daniel Dias Callahan is a writer from Sacramento, California. He received his Master of Fine Arts from the University of San Francisco and a Bachelor of Arts in Sociology from the University of San Diego. His work has appeared in California Quarterly, Sonora Review, and Thin Air Magazine, among other publications. He is a former poetry editor for the online journal Invisible City and teaching fellow at the University of San Francisco.

Image: “Remote Island” by Daniel Nester